This  year began with a pair of earthquakes that has riveted and upset many. But what most upset former banker and current humanitarian philanthropist Sara Henderson was that the panic and devastation streaming across TV screens was so familiar.

year began with a pair of earthquakes that has riveted and upset many. But what most upset former banker and current humanitarian philanthropist Sara Henderson was that the panic and devastation streaming across TV screens was so familiar.

“I felt like I was seeing something I’d seen five years before,” Sara Henderson told me last week.

Henderson, founder and CEO of the Building Bridges to the Future Foundation, said the early scenes from Haiti felt too much like what she had seen five years earlier immediately after the tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia. “People have forgotten that in Aceh it started with a 9.8 earthquake,” Henderson said. “By the time the tsunami hit, massive amounts of infrastructure, governmental structures, many buildings had been leveled.”

As similar stresses tore apart government buildings in Port-au-Prince, she said, the amount of confusion among the media and competing non-governmental organizations also felt sadly familiar. “It got me wondering — have we learned nothing?”

Henderson also felt the same impulse that millions of others did — to try to help. But in her case, she actually had an idea of how to do it, after creating the Building Bridges to the Future Foundation and becoming what the New York Times recently called “one of Aceh’s longest-serving aid workers.”

Now, Henderson’s headed to Haiti at the invitation of Oxfam America and other NGOs [non-governmental organizations] familiar with her work in Aceh. While those peers have offered to get her started, said Henderson, she has no idea what she’ll find. And starting in late March, she has agreed to blog from Haiti for Women’s Voices for Change. (To read my first article on Henderson and her foundation, click here.)

Henderson also has no way of knowing how much of the model she developed in Aceh will be useful in Haiti. Then again, in 2004, when she first began the simple task of rebuilding homes wiped out in Aceh, she didn’t even yet know what a development model was.

“When I was in banking I gave at the office,” she told WVFC. “This was my first venture into anything like this.” But Henderson’s 25-year career international banking had also given her a keen instinct for what was necessary for a project to actually work – including the project of helping a society recover simultaneously from a natural disaster and a 25-year civil war.

Five years later, Henderson is “founder, president, and sometimes barn builder, field clearer and goat delivery girl,” as she describes herself, for an international agency that focuses on getting some of Southeast Asia’s poorest villagers the tools they need for self-sufficiency. Building Bridges, also known as Yayasan Jembatan Masa Depan (JMD), was from the beginning an Indonesian organization, too, grounded in the friends who first brought Henderson to Aceh after the tsunami, the villagers who welcomed her into their lives, and the educators, social workers, and community leaders who deliver its programs.

Five years later, Henderson is “founder, president, and sometimes barn builder, field clearer and goat delivery girl,” as she describes herself, for an international agency that focuses on getting some of Southeast Asia’s poorest villagers the tools they need for self-sufficiency. Building Bridges, also known as Yayasan Jembatan Masa Depan (JMD), was from the beginning an Indonesian organization, too, grounded in the friends who first brought Henderson to Aceh after the tsunami, the villagers who welcomed her into their lives, and the educators, social workers, and community leaders who deliver its programs.

Early on, said Henderson, “most NGOs had withdrawn from Aceh,” especially before the August 2005 ceasefire in the area’s civil war. Even after that, political and religious divisions complicated nearly every interaction between local villagers, many of whom had been in the insurgency, and the myriad international agencies flooding in to help. But from the beginning, Henderson–who’d begun her work in Aceh when wartime conditions still required her to pass through 32 military checkpoints–has worked on behalf of anyone who was poor and desperate enough to ask for her help in rebuilding their homes and their lives.

Thus also was born one 0f BBF’s first principles: Not taking sides. “We don’t care what side you were on,” says Henderson, “if you meet our criteria for help and you will do the work.” So the families, individuals, and community leaders participating in BBF programs come from both sides of the pre-2005 conflict, and from the diverse schools of the Islam practiced throughout the islands.

Thus also was born one 0f BBF’s first principles: Not taking sides. “We don’t care what side you were on,” says Henderson, “if you meet our criteria for help and you will do the work.” So the families, individuals, and community leaders participating in BBF programs come from both sides of the pre-2005 conflict, and from the diverse schools of the Islam practiced throughout the islands.

Another first principle for Henderson: When you start something, don’t be afraid to veer into something completely different. In the year spent building 41 houses in Rumpit, Henderson saw that the women she was helping were illiterate. From that grew an overall commitment to ensuring that women and girls receive the education they need. Now, the foundation’s explicit mission is trifold: to create village-level small businesses in livestock and farming; tailored education programs for women, men and children; and innovative livelihood and skills-training programs.

Each of the three aspects, Henderson discovered, is essential for the others to succeed.

BBF’s Dairy Goat Program, while inspired by the pioneering work of HEIFER international, is more interested in making sure that goat farming in the villages can succeed. “I saw these NGOs come in, and saw the goats being sold,” Henderson told WVFC— describing something quite contrary to the spirit of such programs, which are about helping poor villagers sell milk and dairy products. “It’s not always a sustainable business model,” Henderson added. Rather than such direct giving, BBF’s program helps set up cooperatives and brings in experts to help. One early result: “One of our partners set up one of the first professional dairies in Aceh.”

BBF’s Dairy Goat Program, while inspired by the pioneering work of HEIFER international, is more interested in making sure that goat farming in the villages can succeed. “I saw these NGOs come in, and saw the goats being sold,” Henderson told WVFC— describing something quite contrary to the spirit of such programs, which are about helping poor villagers sell milk and dairy products. “It’s not always a sustainable business model,” Henderson added. Rather than such direct giving, BBF’s program helps set up cooperatives and brings in experts to help. One early result: “One of our partners set up one of the first professional dairies in Aceh.”

- The organization’s education program now works with the Ministry of Education developing and providing educational materials to schools. “They use something called the Packet ABC system,” Henderson said. “Schools get a packet – if a student passes what’s in it, then they graduate to the next level. If we’re teaching third grade, for example, we’ll have materials and tutors appropriate to that packet.” BBF also runs a few of its own schools, and offers scholarships for girls who otherwise wouldn’t be able to complete school.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly for a project founded by a banker, there are many specific programs for financial literacy and education in business management. “We’re helping these businesses get started — a dairy is a business, after all!”

Henderson is going to Haiti with the same friend who went with her to Aceh. She’s nervous but hopeful. “I know that Haiti and Aceh are very different… What happened in Aceh is more like what just happened in Chile, with destruction of the coast,” she said. She considered making the trip to Chile instead, but “everyone kept telling me that in Haiti they need us so much more!”

From the beginning, Henderson’s foundation has tried to work in areas neglected by other NGOs — even when civil war was making more powerful organizations fearful. And that’s the approach she’ll take in Haiti, she said. “I know we won’t be in the capital, with those thousands of aid workers,” she said. “I need to go out into the villages you don’t see on the news.”

When we asked her to file short briefs from Haiti for WVFC, Henderson was delighted. She hopes to inspire other women over 50, though she knows her own reinvention is a little singular: “There’s so much we can do,” she said. “And lots of it isn’t far from home.”

We

We  When Rebecca Skloot walked into the Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia last week to talk about

When Rebecca Skloot walked into the Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia last week to talk about

“I first heard about the HeLa cells when I was 16, at community college taking a class for high school credit,” said Skloot. “My teacher said what all teachers said in those days: ‘There are these cells, there was this woman, her name was Henrietta Lacks, and she was black.’ And I was like, That’s it? That’s all we know? He told me to go find out some more and write an extra-credit paper about it,” she laughed. “About a year ago I sent him my manuscript for this book: ‘Hi, remember that paper I owe you?’”

“I first heard about the HeLa cells when I was 16, at community college taking a class for high school credit,” said Skloot. “My teacher said what all teachers said in those days: ‘There are these cells, there was this woman, her name was Henrietta Lacks, and she was black.’ And I was like, That’s it? That’s all we know? He told me to go find out some more and write an extra-credit paper about it,” she laughed. “About a year ago I sent him my manuscript for this book: ‘Hi, remember that paper I owe you?’”

Guernica Magazine did, anyway.

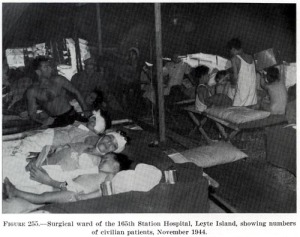

Guernica Magazine did, anyway.  I’ll write more this weekend about the situation at Fort Lewis, which should concern us all and has already got the attention of Amnesty International. But looking at

I’ll write more this weekend about the situation at Fort Lewis, which should concern us all and has already got the attention of Amnesty International. But looking at